Episode – 2052 : Andersonville Prison

Podcast Transcript

During the American Civil War, numerous camps were established to hold prisoners of war from both sides.

Of these, the most notorious was Camp Sumter, better known as Andersonville Prison.

Andersonville, as with all prisons in the conflict, were some of the first dedicated prisoner of war facilities in history, and in the case of Andersonville, it was one of the worst.

Learn more about Andersonville Prison and what made it so bad on this episode of Everything Everywhere Daily.

Before the US Civil War, holding prisoners of war in camps was limited, ad hoc, and usually temporary, because wars were smaller, armies were seasonal, and long-term mass captivity was rarely necessary.

In ancient and medieval warfare, captured soldiers were often killed, enslaved, ransomed, or incorporated into the victor’s forces rather than held in dedicated camps. Detention existed, but it usually meant confinement in cities, castles, or makeshift stockades rather than in purpose-built prison systems.

During the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, including the American Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars, formal parole and exchange systems were the norm. Purpose-built prison camps were rare. Prisoners were scattered among existing facilities or billeted in towns under supervision.

The capture of opposing troops was a common occurrence during the American Civil War. From 1861 to 1863, a parole exchange system was used, which often led to prisoners of war returning to combat relatively quickly after being exchanged for prisoners from the other side.

The Confederacy reversed its unofficial rule regarding prisoners of war in 1863, refusing to treat Black and White prisoners equally. Their argument was that Black soldiers were “ex-slaves” who “belonged to their masters,” and therefore, the Confederacy saw no reason to return them to the Union army.

The Confederacy, suffering from a severe manpower shortage, needed prisoner exchanges far more than the Union did at this stage. Compounding this, a significantly larger proportion of Confederate soldiers, compared to Union soldiers, were currently imprisoned.

So, the Union Generals decided to stop conducting wholesale prisoner exchanges, knowing that the prisoner gap gave the North a manpower advantage.

This meant that both the North and South needed long-term prison facilities to hold their prisoners of war.

The most notorious of these prisons was Andersonville Prison.

Opened by the Confederates in 1864, it was officially named “Camp Sumter” due to its location in Sumter County, Georgia, and was almost universally known as Andersonville Prison, or simply Andersonville.

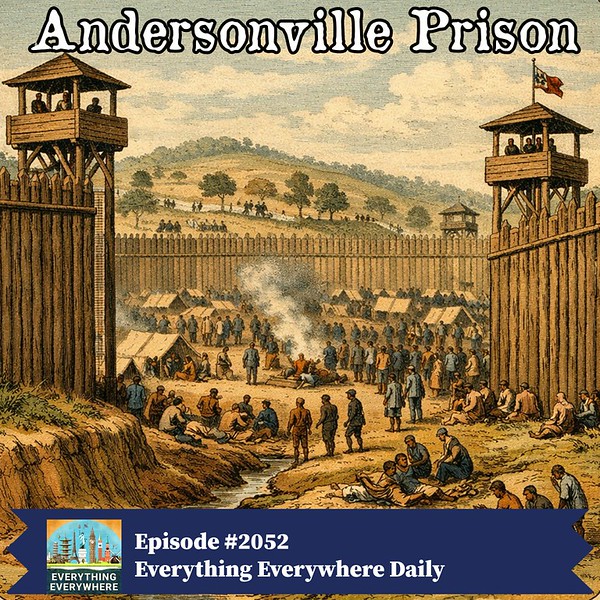

Andersonville Prison, located near Andersonville, Georgia, initially occupied 16.5 acres. It was enclosed by a fifteen-foot (4.6-meter) high stockade. To cope with severe overcrowding, the prison was expanded to 26.5 acres in June 1864.

The stockade surrounding the prison was built of tall logs placed vertically, side by side. The tops of the logs are sharpened to serve as a deterance. Inside the stockade wall was a “deadline.”

The deadline was the line located 19 feet from the inside wall that prisoners were not allowed to cross. If a prisoner stepped over the line, guards located at nearby guard towers known as “pigeon roosts” would shoot the prisoner.

In early 1864, the Confederacy decided to establish a new prison to house Union prisoners of war. This move was prompted by the desire to transfer the prisoners from their previous holding area near Richmond, Virginia, to a more secure location.

The Richmond area was experiencing heavy fighting, which severely strained the local food supply. Relocating the Union prisoners away from the active front was a necessary decision, as it prevented the depletion of valuable food and resources needed by the Confederate army.

The first prisoners at Andersonville arrived in February of 1864. Following its opening, an estimated 400 prisoners were sent to the camp every day. This quickly led to the prison becoming overcrowded.

By August 1864, just six months after it opened, the camp, which was built to house 10,000 prisoners, now contained 33,000.

Andersonville Prison was characterized by extremely harsh conditions. The Confederacy failed to adequately supply prisoners with food, fresh water, clothing, medical care, and housing. This critical lack of resources stemmed primarily from the Southern economy’s collapse, which prioritized Confederate soldiers, and was made worse by the breakdown of the prisoner exchange system.

Survivors’ accounts consistently describe the camp as horrific, characterized by pervasive filth and vermin. Soldiers reported being infested with lice, necessitating constant picking. The level of infestation was so severe that merely sitting down resulted in being immediately covered in lice.

People who lived in the camp were so malnourished that they were described as “walking skeletons.” It was notoriously hot, sitting in a swamp in the middle of Georgia. The swamp, roughly three to four acres in the camp, was used as a sink for the prisoners. The scent was reportedly suffocating, and excrement covered the ground.

Because of these conditions, it is no surprise that there were serious health consequences. The lack of and inadequate food, led to scurvy.

Scurvy, which is caused by a severe Vitamin C deficiency, was a significant contributor to the high mortality rate. As I covered in a previous episode, without fresh fruit and vegetables as sources of Vitamin C, individuals can suffer from fatigue, weakness, low red blood cell counts, gum disease, and skin bleeding.

The extremely high death toll was also due to bacterial infections such as dysentery and typhoid fever, which thrive in unsanitary conditions. The lack of adequate sanitation, particularly the practice of using the same creek for both drinking water and latrine disposal, likely contributed to the spread of these diseases.

The poor conditions weren’t limited to food and sanitation. Clothing was also scarce.

Upon arrival at the camp, prisoners were not issued new clothing. If people wanted new garments, they needed to be taken from the dead. This led to fights between prisoners over who would get which item from corpses.

Another form of cruelty in the prison was that, despite being surrounded by forest, little to no wood was provided for prisoners to cook with or to keep themselves warm. This made it almost impossible for the prisoners to cook what few rations of poor-quality cornflour they received.

Those who died from starvation, disease, or the general poor conditions were buried in mass graves.

It is important to note that while prisoner-of-war camps were a relatively new concept, there were laws put in place to protect prisoners of war.

In 1863, President Lincoln demanded a law guaranteeing adequate treatment for prisoners of war. The goal of this was to guarantee prisoners’ medical treatment and food while protecting them from potential enslavement, torture, and murder.

Unlike in the north, in Andersonville, there were no protections extended to prisoners, and they often had to fend for themselves.

Forming alliances with fellow inmates was a vital defense mechanism at Andersonville. Prisoners who established connections were more likely to secure food, clothing, and shelter. Furthermore, cooperation boosted morale and offered protection from other inmates. Ultimately, making connections was superior to attempting to navigate the prison alone for survival, safety, and psychological well-being.

Life within Andersonville Prison was significantly shaped by internal politics, dominated by two main factions: the Raiders and the Regulators.

The Raiders were essentially a prison gang that attacked fellow inmates to steal food, clothing, money, and jewelry. The group had armed themselves with clubs and were not afraid to kill to get the loot they wanted.

Operating as a quasi-government within the prison, the Regulators were not a typical prison gang. Their primary objective was to counteract the Raiders by capturing them and subjecting them to trial. To this end, they instituted their own legal system, which included convening juries from newly incarcerated prisoners and electing a judge.

The trials of prisoners resulted in severe punishments. After Raiders were found guilty, they were given punishments that included being hanged, “running the gauntlet,” being put in stocks, or having a ball and chain around their legs.

Eventually, conditions in the prison were so bad that the Commander of Andersonville Prison, Henry Wirz, actually paroled five Union Prisoners. The paroled prisoners had a petition signed by their fellow prisoners in their camp requesting the reinstatement of the prisoner exchange.

This never happened, so the prisoners tried to get out of the camp in other ways.

There were many attempts to escape from Andersonville Prison. The most common practice among prisoners was to dig tunnels beneath the stockade. They aimed these tunnels toward the forest, believing that reaching it offered the best chance of remaining free.

However, when trying to use this escape method, many prisoners found they were too weak to get away due to their poor health. If caught, prisoners were given punishments that included execution, being chained, or being denied their rations.

The other common method of escape was to play dead. With roughly 100 prisoners dying daily, it was common for guards to take bodies out of the camp. This task was conducted with little oversight because death was so common.

Under the cover of night, these “fake-dead” prisoners would attempt an escape.

This tactic was eventually discovered, so to prevent further trickery, it was ordered that surgeons check the bodies of the deceased to make sure they were dead.

The conditions at Andersonville Prison remained overcrowded and horrific until September of 1864. This was due to Union General William Tecumseh Sherman, who caused chaos throughout Georgia during his famous March to the Sea.

The occupation of Atlanta, a result of the military campaign, led to the transfer of many Union soldiers held at Andersonville to camps in South Carolina.

After most prisoners were moved, Andersonville was operated on a much smaller scale. The prison wasn’t officially liberated until May of 1865. The survivors were described as being skeletons living in a hellish environment.

In the immediate aftermath of the war, the United States sought accountability. Henry Wirz was arrested and tried by a military commission in Washington, D.C. He was convicted and executed in November 1865.

The trial was and remains controversial.

Henry Wirz’s conviction drew varied reactions: while supporters saw him as the central figure responsible for the prison’s cruelty and neglect, critics contended he was unjustly singled out.

They argued he was made a scapegoat for the Confederate government’s larger systemic failures, including the collapse of its supply chain and the breakdown of prisoner exchanges, policy decisions made by those far superior in rank.

Ultimately, Wirz became the sole, memorable villain in the public’s consciousness, overshadowing the complex causes in popular historical accounts.

Wirz was one of only three confederates, and the highest ranking, who were tried, convicted, and executed for war crimes at the end of the war.

As for the freed prisoners of war, most chose to return to their former lives, resuming their pre-war occupations.

The grim legacy of Andersonville Prison persists, even after its closure. Over the fourteen months it was operational, 45,000 Union soldiers were incarcerated there. Tragically, 13,000 of these prisoners died, a staggering 13% fatality rate among all those held at the prison.

In memory of those who died in Andersonville, former prisoner Dorence Atwater and nurse Clara Barton returned to the site and marked the graves of the Union soldiers who had died within its walls.

Atwater was fearful that in the aftermath of the war, the death records at the prison would be lost. Therefore, he took the effort to copy down over 12,000 names of dead Union soldiers.

By marking the graves and taking the names of the deceased Union Soldiers, the Andersonville Prison was turned into the Andersonville National Cemetery in 1865, months after the conclusion of the war.Of those who died there, only 460 names have been lost to history and placed as unmarked graves.

Andersonville was one of the first dedicated prisoner of war camps in history and was also one of the worst. While it was never intended to be so, a combination of shortages and indifference led to one of the greatest atrocities of the Civil War. This episode can be found at: https://everything-everywhere.com/andersonville-prison/